By Chris Azzopardi

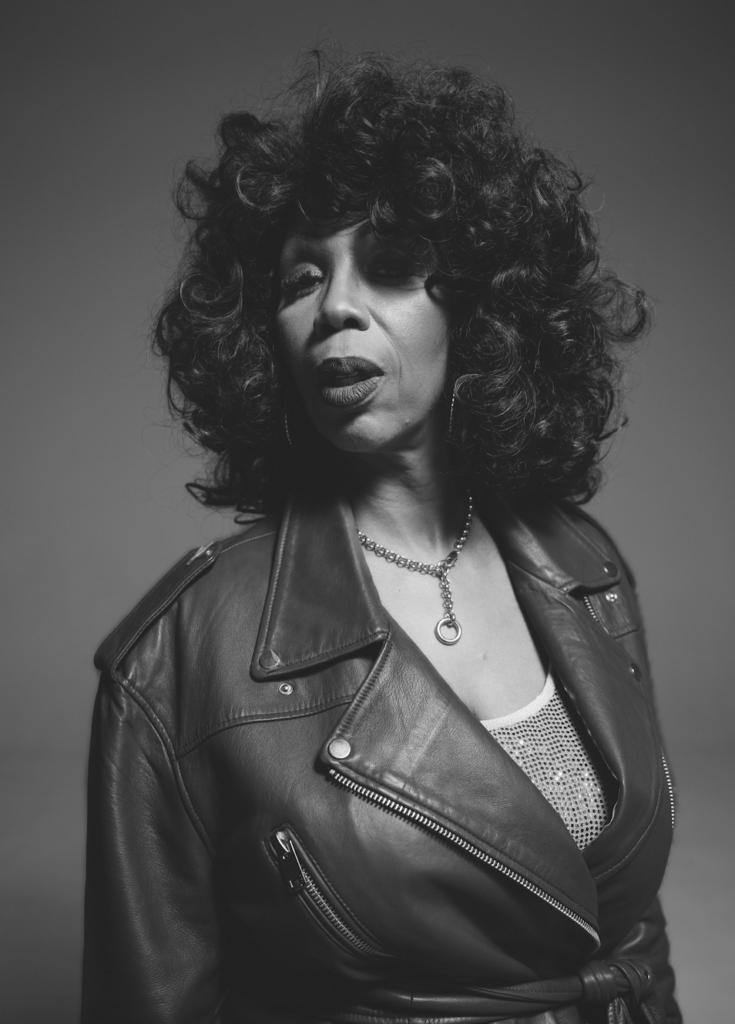

Jennifer Witcher is better known as DJ Minx at the Spot Lite Detroit nightclub and coffeehouse, where she saunters in one weekday afternoon in late February in a cropped leather jacket that exposes the full length of her hip-hugging jeans. Upon entering, the native Detroiter, who shows up performance-ready, looks around like Dorothy waking up in monochromatic Kansas. It’s the different light she’s noticing, warm and deceptively sun-soaked, and this is not her usual crowd, which, when she’s frequenting this spot, is less work-from-home and more… werk.

Even Witcher is surprised she’s here — her typical place isn’t the sofa she’s sitting on; it’s planted in the DJ booth, with a sea of folks, many of them queer Gen Z’ers, letting loose right in front of her. They flood the dance floor to feel the kind of club-community freedom that Witcher, for several decades now, has long inspired through a steady blast of bright techno grooves — the kind of freedom she is now living herself. The empowered state she’s in during our conversation could help just about anyone step proudly out of the closet, even if it has taken them a while to get there.

For Witcher, it took many moons, some men, some women, a supportive daughter and the big hurdle she has now jumped over — the taboo she felt in the post-Stonewall-era years of being a Black queer woman who grew up in a very different Detroit, where you might have been able to be free in the disco light, but on the east-side streets of Mack Avenue and Cadillac, where Witcher grew up, you had to be someone else. Forty years after first thinking she might be gay and just three after coming out publicly in 2021, it’s safe to say that Witcher is exactly who she wants to be right now in whatever light is cast on her.

At Spot Lite, it’s clear she has been loved no matter what. Everyone from the barista to the bartender cordially greets her and her cover story in the British magazine DJ, signed by her, is prominently hung in a large frame in the record store nook of the establishment. “One of the Detroit sound’s original champions” reads the subhead in the article, noting “DJ Minx hasn’t had the attention lavished on some of her peers.”

“Minx’s enduring place in the techno community is something she earned not only by honing her craft so well, but by being such a warm, loving, gracious person to all she encounters,” says Vincent Patricola, a store manager at Spot Lite, where Witcher has been performing as part of a residency at the venue. “Her love for music and the scene is as true as it gets. She is such a star, yet humble to the core. She truly embodies what it means to be a creative class Detroiter in that she can talk the talk and walk the walk with charm and a humble nature.”

As much as Witcher is one of our beloved own, she is also an international star, exporting Detroit techno to all corners of the world, including Zurich and Barcelona recently. Coming out impacted where she performed too — now, you can find her doling out dance vibes at Pride parties everywhere, including upcoming ones in Milwaukee and Detroit (she’s also done some of the biggest in San Francisco and New York — “the New York gays, honey”). She would’ve loved to accept an invitation to perform at Pistons Pride Night this month, she said, but was already booked for a gig in Europe. “I bring in all crowds, all different sets of people with my sets; even if it’s not a Pride party, it’s queer, it’s Asians, it’s Blacks, whites — people from all over. And people have said, ‘We’ve not seen anyone bring everybody together like that.’ I just appreciate everyone’s support.”

One of her favorite places to play is Heideglühen in Berlin — “an adult playground,” she calls it, a place with “a foam bathtub like a sauna and some big swings and a coffee area” that attracts a crowd that is older than the average age, 20 to 35, she’s been playing for regularly since the 1990s. It is a place, one of her favorites she says, where “adults can come and be themselves.”

There is something special about Witcher playing Pride events in Detroit — her home since the late 1960s — where she felt she couldn’t be herself completely until 2021, when she got a call from a Spotify rep interested in including her on a Ruth Ellis Center building mural that would honor her as an LGBTQ+ icon in the Detroit community. She knew what the Ruth Ellis Center was — a place that offers support to LGBTQ+ youth and young adults of color — and Pride Month was just around the corner. It was time, she thought. On June 2, 2021, she was forthright about who she is in an Instagram post, on multiple levels: “People suffer from emotional anxiety at the mere thought of ‘coming out,’ but the stress of not doing so is taking up WAY too much of my space and is shaking my energy to the core. So here I am. Minx, DJ, producer, Momma, partner, lesbian, friend.”

In just two years, Witcher went from a “rough” 2019 — fearful she wouldn’t get booked if she came out — to, a couple years later, feeling liberated and widely supported and affirmed by people like her manager, Jonathan McDonald, and her youngest daughter, who told her she was still a “queen.” “Big time support,” Witcher says.

Her post reached beyond what she could have imagined, immediately attracting hundreds of likes and fans showering her with gratitude for just being herself and helping them through their own struggles with being openly queer. “Everywhere people would stop me and say, ‘You helped me come out,’” Witcher says, beaming.

An official Spotify Pride playlist followed, part of a campaign that month that had each artist, including Hayley Kiyoko, Big Freedia and MUNA, curate a playlist featuring LGBTQ+ artists and allies from their respective hometowns. They were also featured in a mural, painted by the Philadelphia-based artist ggggrimes, in that same city. And then there was Witcher, very visible now, right on the side of the building of a famed LGBTQ+ community organization in her hometown.

This moment was decades in the making, and there’s a sense that Witcher, who is married to her wife now but grew up in the early 1970s when many people like Witcher kept quiet about their queerness, is surprised she came out at all. These days, her wife runs bubble baths for her, and Witcher has her name tattooed on her arm; life for her currently is in stark contrast to that closeted fear-inducing period of time, when the thought of being gay was just that — a thought. “I always had that idea,” she says, “but I was never going to say anything about it.”

A boyfriend in her 20s at least had a hunch, and once told her, “If you want to date a girl and me, that’s fine.” She is still good friends with that ex-boyfriend. “He’s like, ‘You finally got what you want. I’m proud of you.’”

Pivotal to understanding her sexuality was going to raves at the Shelter, in the basement of St. Andrew’s Hall, just as a clubgoer. “I was just hanging out and I noticed the difference in the people,” she says. “They were very friendly. They were nice and colorful.” Even though she says she was seeing plenty of queer people, “I just didn’t feel like there was a place for me in the world at that point.”

Around this time, she began spinning herself. Techno first, then house. Detroit techno artist Derrick May was her initial inspiration. “That’s all I knew,” she says. “So I just had to kind of grow from there and find my own feel of what I wanted to play.”

Witcher found her own path as a DJ, defying gender expectations when it comes to what a woman DJ is capable of in an industry that has a history of putting them in boxes. Because her sound was more in line with what male DJs were playing at the time, she was met with resistance; women even studied her neck wondering where her Adam’s apple is. “When I first started,” she says, “one woman was like, ‘You play like you got a dick. I’ve never heard a woman play like this before.’ I’m like, girl, are you kidding me? You need me to justify whether or not I have a dick? Do you want some?” She laughs devilishly like she almost wishes she said that. “I’m just kidding.”

I ask Witcher what she thinks it says about the way she plays — or the way people interpret how she plays. “It goes back to the man’s world thing. DJing is a man’s world, right? I don’t play the soft, soulful, smooth, little ‘lolly lolly’ music. I go bang and bang, bang, bang, bang, and I mix. And I got on a skirt and some heels and I got on pearls and shit, but I’m still banging because I know how to be classy.”

Even though she played the violin for a brief time in fifth grade, Witcher’s interest in music began in earnest while growing up in Detroit in the 1970s and absorbing the Philly soul and Motown sound that dominated her parents’ record collection. Artists such as Barry White and Earth, Wind & Fire were on repeat. Without knowing it at the time, she was already preparing herself for the booming nature of a club career: “The older I got,” she says, “the more I listened to it louder and louder.”

Eventually, her first apartment in downtown Detroit became the “go-to spot” for a small group of friends to gather to play Nintendo games and listen to a Friday mixed radio show on 97.9 WJLB, hosted by The Electrifying Mojo, which got her into techno and house music. Many of the artists she was hearing were Detroiters themselves, like Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, Jeff “The Wizard” Mills and Cybotron. “The music is moving,” she recalls. “It’s getting to main radio on WJLB, and some of my friends wanted to go to The Music Institute, which I thought was some institution. They’re like, ‘It’s a club.’ So we went to The Music Institute and I heard Derek May play, and I saw the way he’s jolting around and playing. I was like, ‘Wow, this is fascinating, seeing all these people and all the love.’”

As DJ Minx, she started playing sets at places like the Loft and other clubs in the city. What should have been liberating for her instead felt like a crushing defeat — it was the nerves, but also how terribly other Black women treated her. The first time she got on a stage and performed as a DJ was, she says, “stressful.”

“I’m sorry, it was,” she goes on. “When I walked in the club, the women at the front desk wouldn’t let me in. I got my records and they’re like, ‘Well, no, you’re not getting in here.’ And they were laughing at me. It was demeaning. They were bullies, pretty much.”

She recalls the women whispering like mean girls on the playground to each other about her as Witcher defended herself, along with friends who also had her back, and the reason she was supposed to be there, but the women wouldn’t relent. Little did those women know at the time that Witcher would go on to receive recognition for the very thing they tried to stop her from doing. In 2015, Mixmag named her as one of the 20 women who shaped the history of dance music, and Time Out New York included her in a list of the Top 10 house DJs of all time in 2016. For “exceptional achievement, outstanding leadership and dedication to improving the quality of life,” she was awarded the Spirit of Detroit award by the city council in 2018, along with Hale and other women who played a major role in Detroit’s dance scene.

I ask Witcher what she thinks it feels like for those women who once bullied her to drive by 77 Victor Street in Highland Park, where the Ruth Ellis Center is, only to see her giant, iconic face painted on the building — right alongside other Detroit notables like Griz, Dr. Kofi and Ruth Ellis herself. She smiles, seemingly amused at the thought. “To this day, one of them I still talk to often and we’re friends,” she says. “And they have asked me if they could date me.”

At one point during our sit-down, Witcher rolls up her sleeve to show me her tattoos. Fittingly, one reads “Empowered women empower women.” A throughline to her experience as a woman who hasn’t always felt supported by other women is so clear I don’t have to ask about it. You can’t forget that history, but you can try to do your part to change it for future generations of women musicians, which Witcher continues to do. She formed Women on Wax, a collective of female DJs and producers from the Detroit area, in late 1996, and she launched her own label, Women on Wax Recordings, in 2001, which supports and uplifts local talent.

In May, she’ll return to the Movement stage during its closing day on May 27 in Hart Plaza, with plans to bring a newfound authenticity to her set. Since 2000, she’s been DJing at the festival, one of the longest-running dance music events in the world. This time, though, her performance will be, perhaps, the most honest reflection of who she is at this point in her life. “This year I’m switching it up because I need some color. I need some drag queens. I need some drama,” she says. “So this is going to be a different one.”

For this particular set, she’s planning on including drag queens, new visual components and she will also play alongside New York City DJ Honey Dijon, who is trans. “I’m supporting a lot of our people,” she says. In conjunction with her Movement gig, she will continue to host a June Pride party this summer — its launch tells you a lot about how Witcher coming out in her 50s is making its mark. The party kicked off in 2021 right after Witcher wrote that Instagram post. Two days later, she says, reps from Paxahau, the festival’s production company, were on the phone with her manager, asking her to headline a party inspired by her — all because she came out.

“The idea happened naturally,” says Chuck Flask, senior talent buyer at Paxahau. “We were looking to book some parties for Pride Month, and with Minx recently coming out, it made all the sense in the world to have her headline and play her first residency at Spot Lite that June, and we’ve been doing it ever since — they’re always a great time. We’ve been friends with Minx for a long time; she’s an incredible DJ, producer and inspiration — we are happy for her success and the recognition she deserves, locally and globally.”

As for Witcher, she tells me she feels positive change on a personal level — she has, after all, been on the front lines of seeing and living a shift in how women and LGBTQ+ people are treated both inside and outside the club.

“I feel there’s a lot more opportunities for women than there was before,” she says. “And believe me, I know.” In the half-century-long process of helping to get us there, Witcher has also landed on something special she never could have imagined before she hit “share” on that coming out post: “a whole new community to love.”

Chris Azzopardi is the Editorial Director of Pride Source Media Group and Q Syndicate, the national LGBTQ+ wire service. He has interviewed a multitude of superstars, including Cher, Meryl Streep, Mariah Carey and Beyoncé. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ and Billboard. Reach him via Twitter @chrisazzopardi.